Water Wise: The New Landscape Aesthetic for the West

By Greg White, DTJ Associate Principal

As the climate warms, drought conditions rise and water restrictions ensue, we need to rethink the western landscape standard: The use of native landscapes needs to be explored not only as water wise, but as a compelling value for planned developments. Water-wise landscaping can be beautiful, lush, and colorful. The use of native or designed plant communities can have a measurable positive impact on our environment by cleaning and saving water, creating habitats, and cleaning our air. Educating builders, developers, buyers and even cities as to the benefits and return on investment is key to success.

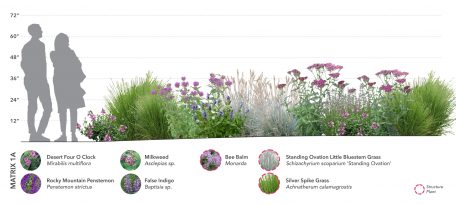

Three Western region projects provide great case studies. The first is the new Kinston at Centerra in Loveland. To achieve a more sustainable landscape and address the rising cost of water, the developer of Kinston wants to establish a new landscape model for its large-scale projects. Teaming with the High Plains Environmental Center and DTJ to develop a landscape approach focused on water reduction and ecosystem function, a new approach to the project landscape was developed, focusing on native plants, low-water-use turf and grass mixes, and eliminating the majority of bluegrass. Additionally, mixed shrub and perennial beds were designed for self-regeneration and minimal maintenance, along with year-round color and texture. Goals for this approach included: reducing water consumption and long-term costs, creating more ecosystem function; reducing long-term maintenance, reducing chemical inputs, and providing habitat for wildlife and pollinators.

To achieve these goals, a critical step is to educate buyers/residents to understand the landscape and embrace the appearance and function. Why does it look the way it does? It provides four-season texture vs. short-season color; it fits the context and enhances sense of place; water and money resources are saved; and ecosystem functions are improved. It also was critically important that the developer understood the up-front maintenance commitment for the initial plant establishment period, intelligent irrigation technology, long-term mulch strategy, and technical installation considerations for successful landscape longevity and return on investment.

The city of Westminster

The city of Westminster has a vision of “a thriving community of safe neighborhoods and beautiful open space that is sustainable and inclusive.” When looking at a recent project in the public realm on the U.S 36/Sheridan corridor, the city wanted to enhance its identity, sense of place, and Colorado context. DTJ’s landscape approach and design were inspired by the foothills native landscape.

This was done by creating landforms that mimic the ridges and canyons and placing native plants in context with the landforms; piñon pines on top and little blue stem on the bottoms to imitate the foothills grassland. Other native plantings included New Mexican privit, pawnee buttes sand cherry and giant sacaton grass. The result with the berming and sculpted planting forms are both iconic and water wise, ensuring the city’s sustainable future and further setting a high standard for future water-wise development.

Pacific Northwest

Farther west, two developer-built parks in Duvall, Washington, are planted with 100% native plants. Why? Because the PNW is experiencing more drought; it’s a summer dry climate. Again, this is where education is critical. The design team helped educate the city as to why the park planting design was more cost-effective than utilizing only turf. Several important principles were outlined, which convinced the city to go with the native landscape aesthetic and utilize turf only in active use areas of the parks. DTJ consulted with a national landscape group to help the city understand the return on investment of upfront costs vs. costs for maintenance and mowing over the long term to reinforce the native planting approach and benefits.

Primary factors for consideration on this approach were:

• Deliberate use of lawn for active use areas: Areas of nonfunctional lawn typically are smaller and less deliberate in form, which makes them even more labor intensive to both maintain and irrigate, making them more costly than larger lawn spaces.

• Native plants: Native plants adapted to PNW climate of wet winters and dry summers require less water than most non-natives once they are established, resist native pests and diseases better, improve water quality by needing less fertilizer and no pesticides, and provide wildlife and pollinators habitat.

• Maintenance levels. Established plant beds are less costly than lawn to maintain over time. The regional cost for maintenance is 30% to 40% higher for mowing and fertilizing lawn as compared to maintaining shrub beds.

• Irrigation requirements. Established plant beds are less costly to irrigate over time than lawn. The water use required for irrigating lawn is as much as four times higher when compared to irrigating established native/drought tolerant plantings.

Sustainable landscapes do not have to be 100% native; they can utilize regionally adapted plants from similar environments. The use of a blend of native and adapted plantings can serve the same purpose. Important too, is to eliminate the lawn, especially nonfunctional lawn in streetscapes. The Duvall streetscape consists of a blend of appropriate materials that both look great and provide tremendous environmental benefits like cleaning the air, water, stabilizing the soil, and habitat. Duvall streetscape embraces this with color, texture and no lawn.

The reality of water scarcity is hitting closer and closer to home. It’s time to do the right thing in terms of water-wise landscape design and embrace a new aesthetic for our communities and neighborhoods. Design can consider layers, textures and color within the context of a sustainable landscape. We must strive to create landscapes that match the site, take clues from native plants, and understand the true availability of water.

BACK TO BLOG

BACK TO BLOG